Closer – Joy Division (1980)

Joy Division’s Closer is listed at No. 16 on the 2018 version of Rolling Stone‘s Top 100 Albums of the 1980s. I had never been a big Joy Division fan, but I was curious. As part of my research for this review, I watched Control, a 2007 biopic centered on Ian Curtis, the lead singer of Joy Division.

I watched as Sam Riley mimicked Curtis’ on-stage antics. He was, in essence, Ian Curtis, an eerie spot-on portrayal that bordered between utter exhaustion and despondency to pure out-of-control mania. I suddenly saw in Riley’s performance the demons that haunted Curtis. He found solace in the minimalist music the band played closing his eyes as if to get ready for the barrage, started singing in an unintelligible growl, and then let the demons show themselves as he danced wildly on stage.

The demons sometimes took control of Curtis in the form of epileptic seizures, which, along with personal problems, pushed Curtis to suicide at the age of 23. After his death, the group reformed as New Order and went in a different direction, finding success with the electronic hits “Blue Monday” and “True Faith.”

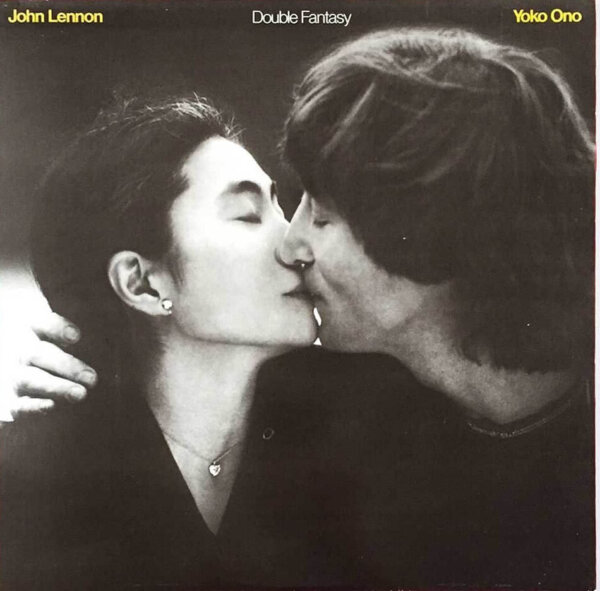

Closer‘s album cover

The album cover for Closer stoked some controversy, as it seemed as if the band were capitalizing on Curtis’s death. The cover shows people mourning over a dead body, but in reality the cover was chosen before Curtis died. It is a photograph of a tombstone in Northern Italy, created by Demetrio Paernio in 1910. But the music is like a requiem for Curtis, if unintentional.

“Atrocity Exhibition” begins with an almost tribal beat, with guitars rattling and screeching its jungle-like sounds. “Isolation” changes direction 180 degrees, with a heavy emphasis on synthesizers. On “A Means to End” Curtis keeps repeating, “I put my trust in you.” With his struggle with his marriage, he yearned to put his trust somewhere and be protected from those demons that got worse as he got older.

“Twenty-Four Hours” is Joy Division unleashed, speeding along at 139 beats per minute with Sumner’s guitars roaring until it reaches a sudden calmness. But it doesn’t last long, as the guitars return and Curtis exclaims, “Gotta find my destiny before it gets too late.”

Minimalism

The key to Joy Division is their minimalism — just one guitar, a bass, and drums. Bernard Sumner plays the guitar sparingly, and you hear the despair in the space between the notes. There should be something else there — a keyboard like in “Isolation,” or another guitar. But you hear silence, which is emotionless and hopeless. It sounds a lot like The Cure’s Faith, which wouldn’t really exist without Joy Division’s Closer.

The penultimate track, “The Eternal,” is a slow funereal track with piano and drums that never seem to fade. Curtis sings, “Try to cry out in the heat of the moment / Possessed by a fury that burns from inside.” When you watch Control (and old footage of Curtis), you see this, and Closer is more doleful and despairing than its predecessor, Unknown Pleasures.

Curtis’ off-key delivery still bothers me, but there’s no doubt that they created the post-punk movement that the Cure, Echo & the Bunnymen, Depeche Mode and even early U2. With 1987’s Substance, we got a little more of Joy Division, including the classic “Love Will Tear Us Apart,”

Closer is a taste of what they could have done had Curtis lived. And that is the saddest thing about the album.