The Solo Beatles: Paul McCartney

Perhaps no one in pop music history has been more decorated and recognized than Paul McCartney: Dozens of albums, scores of Top 40 hits, Grammy awards, an Oscar nomination, even a knighthood. Melodies seem to pour effortlessly from his head, as if they were there all along in nature, waiting to be found. Heck, he even dreamed the melody to “Yesterday.”

In light of all the acclaim and fame, why has much of his solo career been so disappointing?

McCartney fought with his own ego — and music critics — for about 25 years before realizing that (a) writing a song usually isn’t easy; (b) no one can replace John Lennon as a songwriting partner.

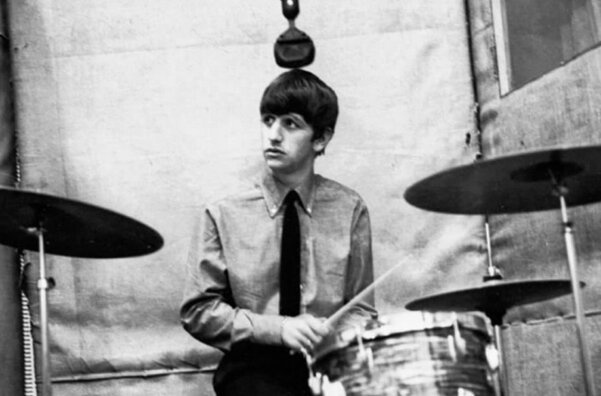

Free from the Beatles because of his now-infamous interview with himself that coincided with the release of his first solo album, McCartney, he was an artist unleashed. He made at least one album per year during the 1970s, both with his wife, Linda, and with a new band, Wings.

But without Lennon’s cynicism reeling him in, the little “granny tunes” that dotted Beatles albums during their later years were even more apparent. He was surrounded by people who nodded approval at everything he said and did. After all, he was Paul McCartney.

Songs that were mocked by Lennon during Beatle sessions and subsequently left off their albums (“Junk,” “Teddy Boy”) made it onto McCartney. They’re charming but forgettable. Without Lennon’s filter, later songs that were half-baked and half-serious were suddenly album filler. His solo career is dotted with fluff such as “Bip Bop,” “C Moon,” “Temporary Secretary,” and “Pipes of Peace” — songs that would have never made it on a Beatles album. The opening lyrics to Bip Bop tell it all: “Bip bop, bip bip bop / Bip bop, bip bip band.” It ain’t Dylan.

The solo McCartney: genius and criticism

There were moments of genius through the years. “Dear Boy” from 1971’s Ram is lush, layered with harmonies and counterpoint. Ram, McCartney’s second solo album, is arguably his masterpiece; once shunned by critics, it has aged well. Likewise, 1973’s Band on the Run is named by many to be his best work. Sandwiched between those are Wings Wild Life, which Rolling Stone called “deliberately second-rate”; and “Red Rose Speedway,” which contained the romantic dirge “My Love.” On that song, McCartney exclaims, “Whoa oh-oh, whoa oh-oh / My love does it good.” Ick.

Unfazed by the bad reviews, McCartney kept churning out the music. There was no one to call BS on him. But it seems he knew there was something wrong; he may have been reading the critics’ reviews of his work. So throughout his career, he sought a songwriting partner to replace Lennon. He went through many; first it was Linda, his wife; then Denny Laine from Wings; Stevie Wonder (“Ebony and Ivory!” Ack!); Michael Jackson; and even Elvis Costello. It rarely worked well.

McCartney thought of himself as a songwriting machine. He felt as if he could simply start playing something and it would come out. As we saw in the documentary “Get Back,” when he wrote the title song, it sometimes worked. But as the benefits of working with Lennon faded away, the results weren’t as monumental, although he kept trying. It became a game to him; he bragged that one time, while waiting for Linda at a photo shoot, he set himself a deadline of two hours to write a song before she came back. (He did it, and the resulting song, “Somedays” from Flaming Pie, was not bad at all.)

Songwriting is not easy, and one good idea does not a song (or an album) make. McCartney featured the brilliant “Maybe I’m Amazed,” which was, in essence, a companion piece to “Let It Be,” and the lazy, breezy “Every Night.” These gems were offset by improvisational jam sessions that seemingly went nowhere and sounded unfinished.

After Band on the Run, he seemed to be mired along with most of the music scene in the mid-1970s. Each album in succession got ripped by critics: Venus and Mars (1975), Wings at the Speed of Sound (1976), London Town (1978) and Back to the Egg (1979) each featured hit singles (“Listen to What the Man Said,” “Silly Love Songs,” “With a Little Luck” and “Getting Closer”) but little else. I won’t even mention McCartney II, in which someone gave him a synthesizer to play with. He redeemed himself with 1982’s Tug of War, which included touching tributes to his fallen songwriting partner, but then followed what was arguably the worst period of his career: The disastrous movie “Give My Regards to Broad Street,” the aforementioned Pipes of Peace (with several bad Michael Jackson duets) and Press to Play.

It was only during the mid to late 1990s — perhaps fueled by the Beatles Anthology project — that McCartney woke up and realized that Lennon’s legacy, though short, might outshine him. The albums came more slowly, with several years in between releases. It showed.

1997’s Flaming Pie was his ode to his former bandmates; if ever there was a Beatlesque record written by a solo Beatle, it’s this one. After getting that out of his system, he proceeded to make his own music for the first time — by Paul McCartney the person, not Paul McCartney the former Beatle. They seemed more crafted than regurgitated: Driving Rain, Chaos and Creation in the Backyard, Memory Almost Full and New rank among his best. If not known for their hits, they are solid, consistent efforts.

Paul McCartney: cementing his legacy

These albums, though, are marked with a certain sadness. McCartney lost his first wife, Linda, saw another marriage end disastrously and lost two bandmates and other friends from his Liverpool years. He’s gotten older, and his voice simply can’t reach the higher notes that it used to hit with ease. There’s a certain chalkiness to his voice now, grown brittle with age. He now speaks fondly of his friendship with Lennon, and he and Ringo Starr have worked to cement the Beatles’ legacy as the greatest band of all time. But many times, it’s just him and his music and the ghosts that he has had to work with. The fact that he is still churning out memorable songs in his late 70s is proof enough that he is something special — even if it’s taken 50 years to prove that to himself and music critics.