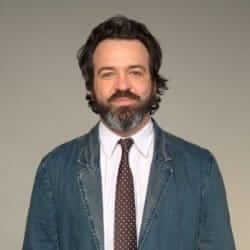

Joe Pernice: The 21st Century Renaissance Man?

It’s 5:45 p.m. and Joe Pernice and Wesley Stace finally climb the stairs to Eddie’s Attic, looking relieved but tired. They’re about 45 minutes late, which doesn’t bode well for my 5 p.m. interview, considering they still have to set up, perform a sound check, and check into their hotel.

It’s 5:45 p.m. and Joe Pernice and Wesley Stace finally climb the stairs to Eddie’s Attic, looking relieved but tired. They’re about 45 minutes late, which doesn’t bode well for my 5 p.m. interview, considering they still have to set up, perform a sound check, and check into their hotel.

Sure enough, I wait patiently for Pernice through the sound check and check-in, and as he and his concert partner Wesley Stace (the former John Wesley Harding) enter the venue five minutes before the show starts – and no interview yet – I know it will be a long night. Encores, greeting fans, signing and selling albums – I’ll have to wait through that.

I wonder if waiting is something Pernice’s friends and contemporaries are used to, because he is a driven man, always consumed with projects. Like some 21st century Renaissance man, Pernice has recorded CDs as five different acts – a solo album, several albums with his main band, the Pernice Brothers, two with another group called the Scud Mountain Boys, and one with his brother and friends under the name Chappaquiddick Skyline.

His latest venture is with Teenage Fanclub frontman Norman Blake under the moniker the New Mendicants, due out Jan. 20.

He’s written several books; contemplated a musical; written, produced and starred in a series of puppet shows based on banter between him and his manager. He’s portrayed himself in an episode of “Gilmore Girls,” and recorded a song about former Boston Red Sox player Manny Ramirez (which made it onto the soundtrack to “Fever Pitch”). After a 15-year hiatus, his side band Scud Mountain Boys released a follow-up to their acclaimed “Massachusetts” LP last year. Once the New Mendicants CD is released this month, he’s scheduled yet another Pernice Brothers release for the summer.

So why tour now? Who has time for that?

“I’d known Wesley’s stuff for a long time, but our paths had never crossed,” Pernice explains after everyone has cleared out of Eddie’s Attic. The two met when Stace, also a writer, appeared with fellow British writer Jonathan Coe at a book reading one evening. “We hung out, we talked, and we just kind of became friends after that.” They toured once before, and several days earlier, the show in Tampa was half concert, half book reading.

This appearance in Atlanta, though, consists only of music, performed in a “songwriters in the round” format. Pernice plays the sidekick to Stace’s biting wit; in fact, to most of the attendees who have come to see Stace perform, Pernice doesn’t look like a singer at all. Stocky, self-deprecating and almost awkward with his glasses, plaid shirt and Boston accent, he amazes the crowd of Stace fans who have never heard of him.

Tough but Tender

Pernice’s music is also surprising; For someone with such a tough Northern exterior, his songs are often quiet and plaintive, with naturally flowing melodies and heartbreaking chord changes. It’s been described by critics as “deceptively beautiful” and a “bridge between pop and pain.” I ask Pernice where these melodies come from, and he’s at a loss to explain.

“I feel like most songs are kind of accidents,” he says. ” I just like to play. I noodle around on the guitar very crudely because I’m not a very good guitar player. But I stumble upon things, and melodies just kind of suggest themselves, it just kind of happens. As far as the music goes, there’s not a heck of a lot of thought involved in it – just a feeling, a vibe, and things that I hear, and then I hear the next step and go after it. Sometimes it sounds good, and sometimes the next step is cliched and not very good, so I ditch it.”

He takes a swig of a beer; he must be parched and starving, having run mostly on adrenaline during the show. “It’s like a chase in a way. I feel like it’s always like a fortuitous act. Rarely will a whole song or tune drop itself on me and myself in my head while I’m walking. It’s always at an instrument when it comes up.”

Pernice’s music is hard to describe; his voice is husky, almost subdued at times, but it’s true and honest, accompanied by acoustic guitar laced with piano and strings. Some songs border on alt-country, with steel guitar, while others have more of a power pop sound. But much of it rides a thin line between happiness and grief. In fact, the Pernice Brothers’ debut album, 1998’s “Overcome by Happiness,” features an opening cut called “Crestfallen.”

Pernice bristles at the mention of “alt-country,” which is usually reserved for acoustic-based music performed by singer-songwriters with a decidedly country sound – think Wilco, Steve Earle or even Lyle Lovett instead of Keith Urban or Sugarland. Pernice dismisses the term as “lazy journalism.” He holds up a copy of the Pernice Brothers’ 2003 release “Yours, Mine and Ours,” which took a decidedly pop turn. “This record? Alt-country? Are you joking?” He admits not reading anything written about him in the press for years, but he has his opinions about their opinions.

Joe Pernice and the New Mendicants

He perks up at the mention of Norman Blake and the New Mendicants album, titled “Into the Lime.” “I love it. It’s got a lot of very strong melodies, a lot of harmonies.” Pernice and Blake live in Toronto, having both married native Canadians, and the two instantly hit it off. “Norman is an outrageous guy to sing with. He just goes for it and gets it, and his ideas are crazy good. He’s a pretty daring guy. He’ll try anything.”

The two wrote several songs for the upcoming film adaptation of Nick Hornby’s A Long Way Down, but the songs weren’t chosen for the movie. No worries – they’re on the upcoming album.

Pernice’s opening song tonight is one of those rejects – a heartaching, beautiful ballad called “Follow You Down,” a song that somehow makes jumping off a building sound like a beautiful act of love. The two swap songs and stories for over two hours, with Pernice playing a mix of mostly Pernice Brothers and New Mendicants songs. But the highlight of the evening is when Pernice plays the opening chords to “Prince Valium,” the opening track from his 2000 solo album “Big Tobacco.”

Technically, the chord progression follows a descending tetrachord bass line, also known as a “lament bass.” It’s called this because the bass, which descends down the scale from the main key one note at a time, creates tension as it moves away from the root (in this case, an E). It yearns to find its way back but keeps moving farther away.

Tonight, Pernice plays it a whole step lower (in D), which somehow makes the song heavier and even more depressing as Pernice sings of love, loss and desperation, hiding behind the guise of addiction. “Always knew you’d be going, though I did not know just when / So help me Lord, get me stoned again,” he sings.

But as it is with most Pernice songs, there’s a deeper beauty lurking beneath the sorrow. It’s this power of just a few chords – chords that Pernice suggests come by accident – that causes my vision to blur with a tear. I’m not sure whether it’s sadness or joy. Pernice has chased down the perfect chords in “Prince Valium,” and I am still humming the song as I arrive home at midnight, emotionally exhausted but satisfied.